Process modeling with Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs) and the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN)

| |

Copyright 2014 - 2026 by Josef L. Staud |

|

Author: Dr. Josef L. Staud |

|

Status: January 2026 |

|

Web and Book |

|

This text is published both as a printed book and as an online resource. Bibliographic information is available at www.staud.info. The web version is slightly abridged; in addition, the book version includes a comprehensive index. |

|

Process Models |

|

Working with event-driven process chains and Business Process Diagrams (process models of BPMN) inevitably results in large-scale diagrams. In addition to their inclusion in the text, these diagrams are published separately in a larger format and with higher graphical quality at the following addresses: |

|

https://www.staud.info/grafiken2020/GrafikenEPK.php

https://www.staud.info/grafiken2020/GrafikenBPMN.php |

|

Web Preparation |

|

These HTML/PHP pages were generated using a program I developed myself: WebGenerator (version 2026). It converts texts into HTML/PHP pages and is under continuous development. This "automated" generation makes it possible to immediately regenerate the HTML pages after every change to the text. Since it is not feasible to review all pages after each regeneration, it is quite possible that errors may occur on some more "remote" pages. I apologize for this and would appreciate any feedback or notifications (hs@staud.info). |

|

Copyright |

|

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise - without the prior written permission of the author, except as permitted under the German Copyright Act (Urheberrechtsgesetz) of September 9, 1965, as amended. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of this publication, or any portion of it, may result in civil and criminal penalties under applicable law. Requests for permission should be directed to the author. |

|

Trademarks and Brand Protection |

|

All product names, trade names, trademarks, and brand names mentioned in this text are protected by trademark, brand, or patent law, or are registered trademarks of their respective owners. The appearance of such names and designations in this text - without explicit identification - does not imply that these names are free for general use under trademark or brand protection laws. |

|

Prof. Dr. Josef L. Staud |

|

|

|

1 Introduction |

|

1.1 Preliminary Remarks |

|

The topic of process design and process optimization is of central importance for all companies and other organizations. It is a continuous task. However, process optimization requires that processes first be identified and described by means of process models. Only after this documentation has been carried out can weaknesses be identified and eliminated, and new approaches to process design - within the context of digitalization and automation - be incorporated. |

|

Significant changes have also occurred in the methods used over the past ten years. New methods have emerged, such as BPMN, while others that never truly gained acceptance in process modeling - such as UML activity diagrams - have largely disappeared. Event-driven Process Chains (EPCs), however, remain the ideal instrument for modeling processes in the context of an as-is analysis: they are simple, quick to learn, and nevertheless provide expressive process models, as will hopefully become clear in this text. One cannot reasonably expect more from a method. If, within the scope of requirements engineering, a more implementation-oriented modeling of processes is desired, other instruments should be chosen - for example, BPMN. |

Methods |

For presenting process examples, I use the terms concrete example and abstract example. Concrete examples illustrate a process (or a process segment) using specific, domain-related situations. They show how a process works in practice by referring to realistic tasks, documents, and decisions. Abstract examples, by contrast, use simplified and generic constructs that are independent of any specific application domain. Their purpose is to highlight the underlying syntactic modeling principles without being distracted by domain-specific details. |

Process Examples |

|

|

1.2 List of Abbreviations |

|

The following abbreviations are used throughout this text. They correspond to standard terminology in process modeling and related disciplines. Abbreviations that appear in Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs) and Business Process Diagrams (BPDs) are explained within the respective process models. |

|

|

|

| Abbreviation |

Full Term / Meaning |

| AD |

Activity Diagram (UML) |

| AND |

Logical AND Operator |

| ARIS |

Architecture of Integrated Information Systems |

| B2C |

Business to Customer |

| BP |

Business Process |

| BPD |

Business Process Diagram |

| BPMN |

Business Process Modeling Notation (from Version 2.0: Business Process Model and Notation) |

| BPR |

Business Process Reengineering |

| eEPC |

Extended Event-Driven Process Chain |

| EPC |

(Basic) Event-Driven Process Chain |

| ERP |

Enterprise Resource Planning. An established term for integrated, process-oriented standard software. |

| IS |

Information System |

| IT |

Information Technology - originally meaning information technology in a narrow sense, but now commonly used as a collective term for an organization's entire data-processing infrastructure |

| OR |

Logical OR Operator |

| rE |

Resulting Events |

| RE |

Requirements Engineering |

| tE |

Triggering Events |

| XOR |

Logical Exclusive OR Operator |

| |

|

|

1.3 Structure of This Work |

|

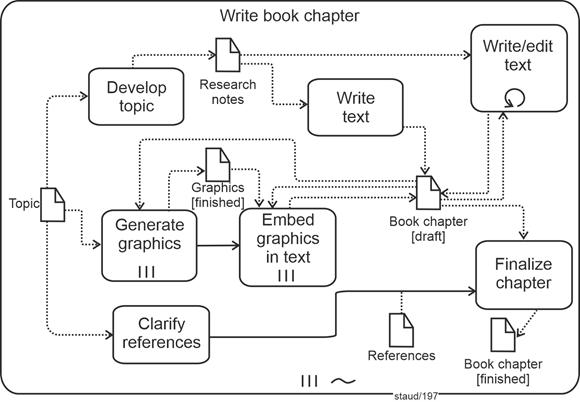

This text is designed to introduce readers step by step to the modeling of business processes using Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs) and Business Process Diagrams (BPDs) of BPMN. The structure follows this intent. |

|

- Chapter 2 presents, in general terms, how the literature defines business processes and process modeling.

Beginning with Chapter 3, the focus shifts to EPCs. |

|

- Chapter 3 introduces the foundational concepts as defined by the originators of the method (Scheer and his team).

- Chapter 4 deepens this understanding by presenting the basic patterns that can occur in EPCs.

- Chapter 5 provides an introduction to process modeling with EPCs through a commented example.

- Chapter 6 summarizes the syntactic rules, offers recommendations for the pragmatics of process modeling, and outlines several design guidelines.

|

|

Further discussions of EPCs and their modeling can be found in [Staud 2025]. This includes, in Chapter 8, numerous examples of EPCs with different modeling emphases. |

|

Beginning with Chapter 7, this text turns to BPMN. |

|

- Chapter 7 describes how the authors of BPMN conceptualize business processes.

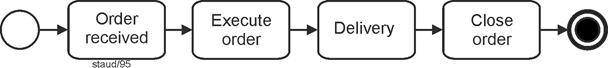

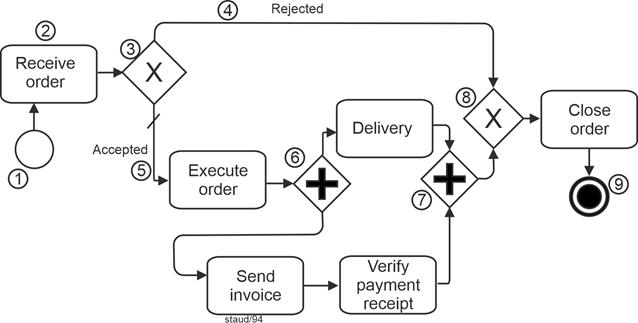

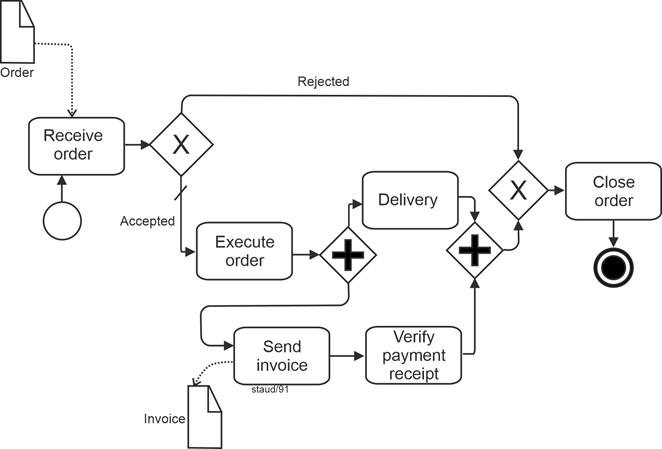

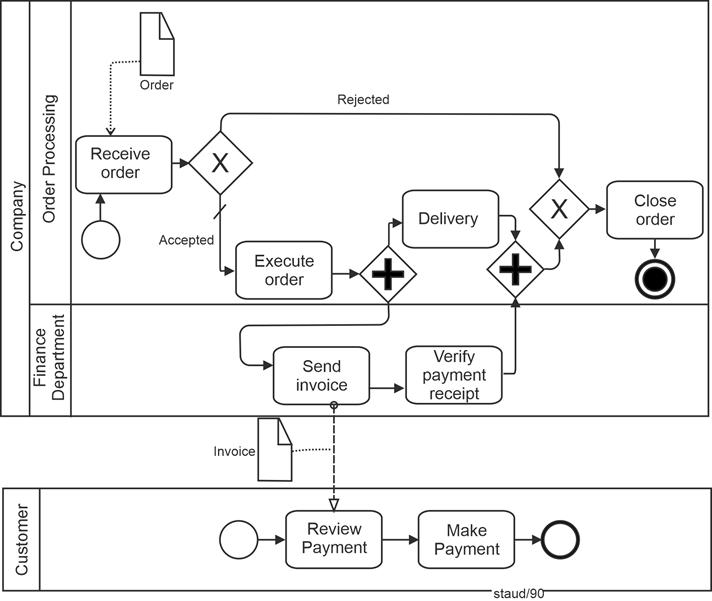

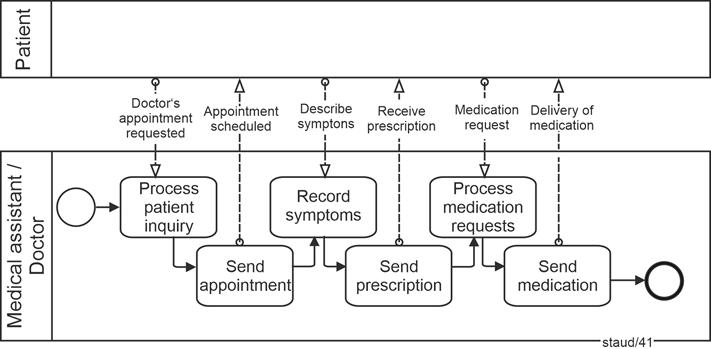

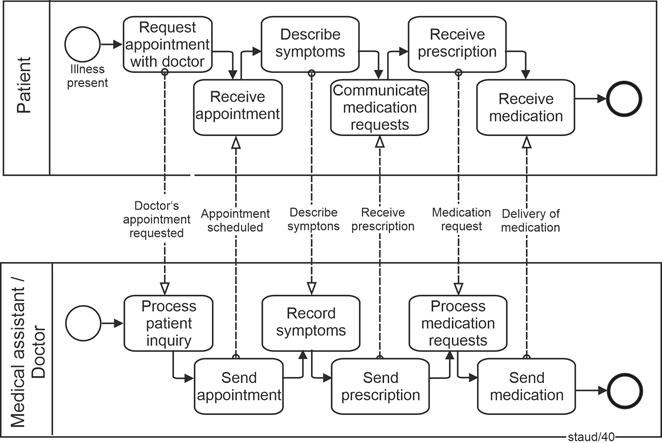

- Chapter 8 presents introductory examples that illustrate the most important components and structural characteristics.

- Chapter 9 addresses the documentation of individual process steps.

- Chapter 10 explains how information and its processing are represented in BPDs.

- Chapter 11 describes how events are viewed and captured in BPMN.

- Chapter 12 is dedicated to the representation of sequence flows.

- Chapter 13 elaborates on gateways, the operators of BPMN, building on the discussions introduced earlier.

|

|

|

|

|

2 Business Processes and Process Modeling |

|

The Subject Matter |

|

What are the "sequences" we call business processes and model using Event-Driven Process Chains or BPMN? How are they defined? What are their characteristics? How are they structured? And what challenges do the present and future pose for process modeling? These questions are addressed here so that we better understand the subject we are about to model - and thereby model it better. |

|

|

|

2.1 Definition |

|

Very simply put, business processes consist of goal-directed sequences of activities. In the literature, for activities performed by people or application programs within organizations to achieve set objectives, the terms task and operation are used. |

Goal-Directed Action |

Activities are generally defined as tasks, which can be viewed at different levels. The lowest level, so to speak, consists of elementary tasks - tasks that cannot be further decomposed, or that are not further decomposed at the level of description in question. Several such elementary tasks are then grouped into a task. We adopt the following definition, which also highlights the natural expectation of a result and the executability by humans or machines [Österle 1995, p. 45]. Here, software has been added: |

Elementary Tasks and

Tasks |

A task is a business function with a determinable result. It is performed by people, software, and/or machines. |

Definition |

Tasks defined in this way can themselves be grouped - across multiple levels - up to the point where the entire corporate purpose is represented by a single task (e.g., "generate profit"). This is called aggregation, and it clarifies what plays an important role in the concrete modeling of business processes: |

|

The tasks to be performed within business processes can be considered at different levels of aggregation. In process modeling, tasks can therefore be split or combined. |

|

Subjective Level of Aggregation |

|

For process modeling, the consequence is that the level of aggregation at which tasks are considered is a subjective factor determined by the modelers or by the purpose of the modeling. Typically, a process model is more detailed where optimization is suspected to be necessary, and less detailed where the goal is primarily to represent the process as a whole (see the example in [Staud 2006, Section 6.2]). Frequently - deliberately - several different aggregation levels are modeled, e.g., to obtain overview representations. This leads to the vertical dimension of process modeling. |

|

Functions |

|

In both process discussions and concrete process modeling, the term function is used in a way that largely overlaps with the task concept but is more closely tied to the modeling environment. Mertens understands a function as an activity |

|

"...that aims at changing the state or condition of an object without reference to space and time. A function designation consists of two components: a verb (operation) and a noun (object) to which the verb refers (e.g., determine reorder point)." (translated by the author from the German original) [Mertens 2013, p. 41] |

|

In Event-Driven Process Chains, individual activities are called functions, regardless of the level of aggregation [Anmerkung] . |

|

By objects we mean business-relevant objects, i.e., business objects. This notion of object largely corresponds (often implicitly in the literature) to the general object concept of object-oriented theory. They are always carriers of information (e.g., an invoice) with attributes and behavior (or permissible changes). For example, invoices with attributes such as invoice number, date, and recipient, which can be paid or canceled. |

Business-Relevant Objects |

Operations |

|

The first step from individual tasks to a sequential series of tasks is made by defining operations. Following Bullinger/Fähnrich, operations are |

Sequential Task

Sequences |

"Sequences of activities that are carried out to realize tasks." (translated by the author from the German original). [Bullinger amp; Fähnrich 1997, p. 19] |

|

They include organizational dimensions (e.g., positions) in their execution. Standardizable operations in companies are also referred to as workflows. They can be described on the basis of four categories: |

|

- Event flows control the activation of tasks depending on occurring events and thereby cause state changes in the system.

- Data or object flows model input information or objects required for task execution, and the use of results in subsequent tasks.

- Task performers represent positions in an organization and carry out tasks.

- Resources are materials or operating resources required for task execution; these may also include task performers.

|

|

A very similar view is offered by Scheer, who defines a business operation as follows: |

|

"An operation is a time-consuming occurrence that is triggered by a start event and completed by an end event. Depending on the operation's results, different control-flow branches, including backward jumps, may follow" (translated by the author from the German original) [Scheer 1998a, p. 20] |

Definition |

Operations, in turn, form business processes. This already states a good deal of what must be considered when modeling business processes: |

|

- The control flow, as it represents the event flows described above. Without knowledge of the correct sequences of the individual processes, or without the business rules that define them, there can be no business processes.

- The data used and the databases, since system state changes are the changes in data arising from service delivery.

- Data flows along business processes and within individual activities - especially across organizational boundaries today, based on the Internet and XML.

- Object flows, the objects involved in service delivery. These include business objects, which again brings us to data and databases, since business objects are, of course, typically stored in the organization's database today.

- Individual activities, based on tasks.

- Service providers as task performers, which today very often include application programs.

- The Organizational structure, represented through the concept of positions.

- The Materials and resources, required for service delivery.

|

|

All this - and a bit more - must be taken into account in process modeling if it is to be truly meaningful. |

|

Definition of Business Processes |

|

The author defines business processes in organizations - based on an analysis of definitions in the literature and on his own practical experience - as follows: |

|

A business process consists of a coherent, complete sequence of activities necessary to achieve an organizational objective. |

Definition |

These activities are performed by task performers within organizational units or by application programs, using the required production factors. The execution of business processes is supported by the organization's IT. |

|

Application programs have been added as task performers. This is indispensable in an era of increasing automation of business processes. |

|

Business processes thus perform the transformation of acquired production factors into products or services that are sold. In this context, business processes also describe the organization's value chain. |

|

From this we obtain key elements for modeling business processes: |

|

- Individual activities that make up the business process.

- The relationships between them, later called control flow.

- Embedding of the business process in the organization's overall activity by stating its objective.

- Task performers - the answer to "Who delivers the work?"

- Reference to automation of business processes (programs as task performers).

- Production factors and their consumption during process execution.

- IT support for process realization.

|

|

A method for modeling business processes must take all of this into account. |

|

The Concept of the Business Process |

|

In the early years of organizational theory, and well into the 1960s, optimization efforts focused on individual activities, their position holders, and the embedding of those activities within operational sequences. Later, the idea of the business process emerged. With the introduction of the business process concept, the perspective shifted. The primary focus now became longer, coherent sequences of activities required to accomplish a larger task - sometimes even a sequence of activities that, from the perspective of the organization under consideration, constitutes a complete and self-contained process. |

|

This remains the state of the art today. Most efforts to improve operational procedures in organizations in terms of effectiveness and efficiency begin with an analysis of the business processes and their optimization. |

|

Today (in early 2026), however, current AI techniques play an important role in this context. Which tasks can now be performed using these technologies? And how can they be integrated into business processes? |

|

Examples |

|

Below are several examples of business processes, aligned with the typical structure found in industrial enterprises: |

|

- Quotation creation (preparation of a quotation after an inquiry has been received)

- Order placement (placing an order with a supplier)

- Procurement (e.g., acquiring parts for production)

- Dunning process (e.g., regular reconciliation of open items and incoming payments)

|

|

And one business process that is typically quite long: |

|

- Order fulfillment or service delivery (from the moment the order arrives at the company to the delivery of the product to the customer)

|

|

Of course, there are also short business processes in the sense that they consist of only a few individual activities, for example: |

|

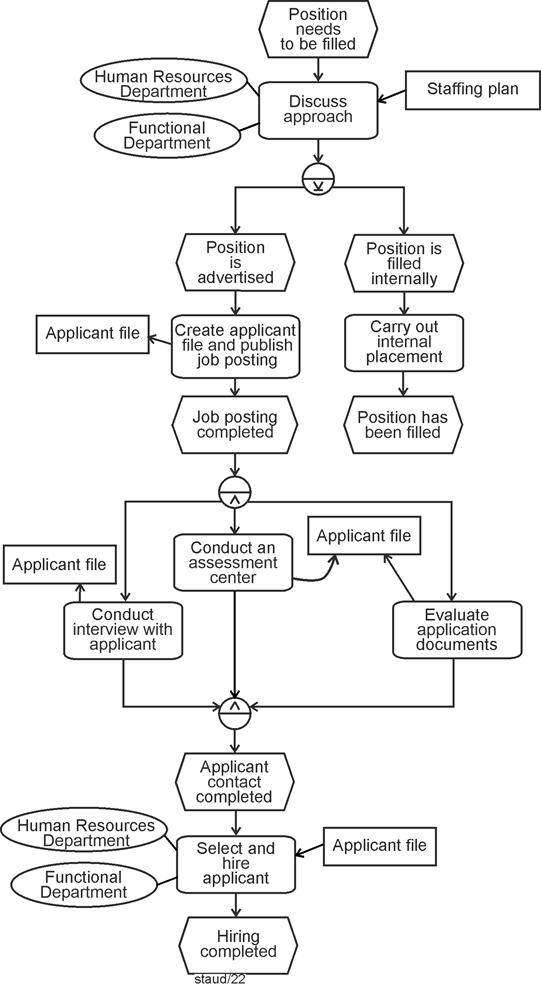

- Customer survey (e.g., as part of Customer Relationship Management (CRM))

- Personnel hiring

- Payment processing

- Approval of an investment

- Invoicing

|

|

2.2 Properties and Components |

|

There are, of course, many properties of business processes and process models worth considering (see the relevant literature

![[2] For example, see [Schmelzer and Sesselmann 2013] or [Becker, Kugeler, and Rosemann 2012].](../grafiken/FZ6.gif) ). We focus here on the most important - those that matter most for process modeling.

). We focus here on the most important - those that matter most for process modeling. |

|

2.2.1 Level of Detail in Process Modeling |

|

This property captures how detailed a business process is modeled. Were only a few milestones captured (as in the early years of process modeling in the 1970s)? Or all major sections at a coarse level? Or is the entire process modeled in detail - meaning that all tasks to be performed by participants are captured and modeled in detail? |

Comprehensive,

Partial, or No Detailing |

Detailed modeling is a prerequisite for implementation in software; only then can models serve requirements management for software development - and, ultimately, full automation. |

|

However, detailed modeling is not always possible. The more standardized the relevant process sections are, the easier detailing becomes, because the sections are known. The less standardization (e.g., in creative areas such as strategy development, research, or development), the less detailed the modeling can be. Still, our daily experience with (almost) fully automated customer-facing processes on the internet and in companies shows that complexity is not, in itself, an obstacle to detailed modeling and software implementation. |

Detailed Modeling Only

for Standardized Processes |

In a process model, the level of detail is visible through the decomposition of activities. If they represent elementary activities, detailing is high. If many aggregations are used - possibly to the point where concrete actions are no longer representable - detailing is low. |

Recognizing the level

of Detail |

2.2.2 IT Coverage |

|

This property captures the proportion of the process that is supported by IT - with an emphasis on support (as opposed to automation, i.e., complete execution by software). Today, application-software support for business processes is standard; what varies is the extent. Are only decision functions still not IT-supported, or are there sections that, despite being amenable to IT support, still lack it? |

Support by IT,

Typically via ERP-Software |

Overall, IT coverage is now very high, particularly since the establishment of process-oriented integrated standard software (ERP). Most sections of business processes are now IT-supported. |

|

IT support can be captured by noting, for each activity, whether it is performed with software support and, if so, which application is used - in addition to who performs it. It can also be inferred from the information objects modeled: under IT coverage, these are part of an application's data store and (hopefully) marked as such. |

Capturing IT Support

in the Model |

As noted above, IT coverage requires detailed modeling - e.g., in procurement, not merely procure parts, but identify eligible suppliers, request quotes, negotiate terms, formulate order, send order, etc., as in standard process modeling (see [Staud 2025, Section 12.1]). These elementary functions can then be mapped at a more detailed level to program constructs. |

Prerequisite: Detailed

Modeling |

If such modeling prepares the development of integrated, process-oriented software, it is part of requirements engineering in the development project. |

|

2.2.3 Degree of Automation |

|

Another important property of processes or process sections is the degree of automation - the share of task performance completed without human intervention, solely by information technologies. In many areas, a high degree of automation is pursued; where flows are highly standardized and decision processes are simple, this goal has largely been achieved. A simple schema is fully automated / partially automated / not automated. |

Fully Automated,

Partially Automated, Not Automated |

In internet-based companies, fully automated business processes toward customers are now in place. The business model would not be conceivable otherwise. |

|

Automation presupposes the detailed modeling mentioned above and is feasible only for standardizable processes. Unlike mere support, decision procedures are encoded in software. For example, reordering for inventory is performed automatically; purchase recommendations are generated automatically (sometimes amusingly so); and handling of apparently non-paying customers is, to a significant extent, software-driven (see the "invoice" process example in [Staud 2019, Chapter 13]). |

Support vs. Automation |

In recent years, automation has been driven to a new level by AI - not only through text and speech technologies but also through software agents for process control and improved process mining, i.e., the digital recording and analysis of process executions. |

AI for Business

Processes |

Automation is reflected by indicating the performers of activities. Where one would typically list an organizational unit, one now lists the application software - i.e., execution without (direct) human involvement. |

Capturing Automation

in the Model |

Consider, for example, a typical B2C internet company: in key sections, besides the customer, only software is active (offering goods, making suggestions, recording orders, filling a (virtual) shopping cart, etc.). This extends deep into automatable sections of finance and logistics - and continues to expand. |

|

In requirements engineering for the corresponding software, after standard process modeling, the next, "lower" level of modeling must be chosen to be program-near. In this text, program-near process modeling refers to modeling that - e.g., within requirements engineering - directly prepares programming. See [Staud 2025, Section 12.5 and [Staud 2019] for the UML methods used at that stage. |

Program-Near Process

Modeling |

2.2.4 Process Integration |

|

Another important characteristic of business processes is the degree of process integration. This refers to the end-to-end nature of a business process across different traditional organizational functions, such as procurement, purchasing, production, sales, accounting, and human resources. In addition - though only for a few years now - it also includes integration across organizational boundaries. |

|

This end-to-end integration is now generally achieved within organizations, while cross-organizational integration continues to be an area of ongoing development. |

|

An example of a lack of end-to-end integration - commonly referred to as media breaks - occurs when a business object cannot simply be passed from one process segment to the next, but must instead be re-entered. These points of discontinuity are called media breaks. They are not necessarily apparent in process modeling, because the same business object may simply appear again in the subsequent process segment. This must be made explicit, among other things, through modeling the transfer of information (see [Staud 2025, Section 7.1]). |

Media Breaks |

Further examples of media breaks include: |

|

- Output of information in one software system followed by manual input into another

- Incoming information (e.g., related to order receipt) that must be processed in order to be transferred into the organization's own application software

- Information required for a forecasting calculation that cannot be provided in the form in which it is needed

|

|

At its core, the situation is this: if the same information that has already been captured must be captured again, there is a deficiency in process integration. |

|

This property can be captured by recording the information objects associated with each activity precisely. For example, for invoice receipt: first the invoice at the central office handling incoming mail; then the invoice in Finance. A transfer was needed between these points. Ideally, the invoice would be stored in the organization-wide integrated database at the first activity and accessed at the second. With media breaks, this fails - the invoice must be re-entered, scanned, etc. This constitutes a media break and should be modeled explicitly. |

Identifying Media

Breaks |

When exchanging information objects between organizations, we speak of semantic process integration if, in addition to the absence of media breaks, the semantics of the information object (invoice, delivery note, coordination information, ...) is recognized by the recipient. Many companies are working toward this in B2B [Anmerkung] contexts. |

Semantic Process

Integration |

2.2.5 Data Integration |

|

Another important characteristic is the degree of data integration, that is, the integration of the data repositories required for the individual activities of a business process. This aspect is of great importance, since non-integrated data repositories lead to friction losses. In concrete terms, this can mean the following: data related to a specific area, task, or business process |

"Friction Losses"

Due to Lack of Integration |

- ... exist in different digital or even non-digital data repositories and are therefore fragmented,

- ... exist in different data repositories and are inconsistent (e.g., differing product data, addresses, etc.).

|

|

Beyond database incompetence or sloppiness, a common source of such deficits is organizational mergers - which also merge IT and databases. Both are complex and often not comprehensively solved, or only belatedly. |

Source |

How can such deficits be detected in process modeling? By precisely recording the information produced or used by each activity. If modeling is sufficiently detailed and accurate, fragmentation will be revealed. Contradictory data stores, however, cannot be resolved within process modeling; they require additional effort, including a close look at database structures. |

Detecting Insufficient

Data Integration |

Here, we reach one of the limits of process modeling (see [Staud 2025, Section 10.2]). Data integration requires a database-oriented analysis of the data repositories in order to take a step toward an integrated enterprise database. |

|

2.3 Objectives of Process Modeling |

|

The first objective of any business-process modeling effort is fact-finding - determining which business processes run in which form. This may directly yield documentation (e.g., for ISO 9000 certification) or descriptions used to prepare the introduction of ERP software. In the latter case, as-is analyses compare the ERP software's pre-defined processes with the organization's documented processes: |

As-Is Analysis |

An as-is analysis is the documentation of an existing process with all its characteristics and deficits. |

Definition |

The second major objective is business-process optimization - eliminating weaknesses identified during process capture. Examples include: |

Optimization |

- Lack of data integration (data islands)

- Lack of process integration (organizational breaks)

- Excessive transport times for process objects (documents, invoices, CAD drawings)

- Excessive waiting and queue times for process objects

- Excessive processing time

- Excessive setup and throughput times

- Redundant activities

- Excessive complexity (e.g., high planning and administrative overhead)

- Insufficient process mindset (poor understanding of upstream/downstream sections)

- Excessively long communication and decision paths

- Excessive total process costs

- Insufficient transparency (which can hinder process change)

- Inadequate process accountability

- Fragmented responsibilities

|

|

Some deficits become apparent immediately during modeling; others only when focus is set according to objectives. These objectives strongly shape the concrete design of the modeling. Depending on the suspected deficit, the emphasis will differ. In [Staud 2006, Section 6.2], a business process is presented where this becomes very clear: the entire order fulfillment is modeled, but the focus was on improving the creation of required CAD documents. Therefore, modeling is very detailed in sections addressing that topic, while in other sections - where the goal was merely to bridge gaps to allow modeling of the entire process - aggregation is coarser, even superficial. |

Process Modeling with

a Specific Objective |

Further objectives - under the heading "Use Cases for Process Models" - are listed in [Becker, Kugeler and Rosemann 2012, pp. 199f]: |

Use Cases for Process

Models |

- Organizational documentation, for example, for up-to-date descriptions of business processes.

- Process-oriented reorganization, whether revolutionary or evolutionary.

- Continuous process management, long-term planning, execution, and control of processes.

- Certification according to DIN ISO 9000 ff., possible only with documented models.

- Benchmarking, comparing one's own business processes with those of other organizations.

- Knowledge management, aimed at creating transparency regarding the organizational resource of knowledge.

- Selection of ERP software, by comparing the organization's own process model with that of the ERP vendor.

- Model-based customizing, parameterization of the software.

- Software development, as part of the requirements specification.

- Workflow management, using process models as the basis for creating workflow models.

- Simulation, analyzing system behavior over time with the goal of process optimization.

|

|

Customer Orientation as the Goal of Process Modeling |

|

Naturally, the central objective of any process optimization effort is to enhance value creation. The path toward this objective, however, leads - as the literature consistently agrees - through a strong orientation toward the customer. See [Schmelzer and Sesselmann 2013, Section 2.2]. |

|

2.4 Challenges for Process Modeling |

|

What are the challenges in process modeling? The most important can be summarized under the keywords level of detail, automation, and the use of AI. |

|

2.4.1 Level of Detail |

|

This was already discussed among the properties of business processes, but it is also a trend with direct impact on process modeling: the increasingly detailed IT support of business processes. Since the beginning of the data-processing era, organizations have tended to extend and deepen IT support (see [Staud 2006, Chapter 2]). Today, almost every task in an organization is supported by an application system. This has only been possible through increasingly detailed process modeling, which, as we know, now covers almost every work step. |

Ever-More Detailed

Process Models |

This trend requires adapted process modeling. The classic as-is analysis must be complemented by program-near process modeling (see [Staud 2025, Section 12.5]). |

|

The term level of detail refers to the degree of refinement with which a business process is represented in a model. A high level of detail means that all individual tasks and decision points are explicitly modeled, while a low level of detail indicates a more aggregated representation of activities. |

Definition |

The appropriate level of detail depends on the modeling objective: detailed models are required for implementation or automation, whereas less detailed models may suffice for documentation or overview purposes. |

|

2.4.2 Automation - Opportunities and Limitations |

|

The property of the degree of automation discussed above is also an expression of a broader trend in the development of IT in general and of process modeling in particular. An automated business process is one that is realized by software without direct human involvement. This is nothing new in technical domains - automated processes have long been present in technical systems (ATMs, for example). |

|

In the implementation of business processes in software, however, this was not the case until relatively recently. It has been implemented in a truly comprehensive manner primarily by companies that operate on the internet or with the help of the internet. All business processes that involve customers are realized through application software, as are subsequent processes in logistics and finance. |

|

In these areas, however, automation is not comprehensive but rather partially supported by humans. One need only think of collection agencies or of important company-side decisions that must be made by people. Work in the large warehouses of online retailers is also still partially human-supported. |

|

A similar situation can be observed in other organizations that do not primarily operate on the internet. The application software used there, based on very detailed modeling of business processes, is partly automated and partly not. This is why the proportion of automated segments could be introduced above as a relevant property. |

Partly automated,

partly not. |

This should already be clear, but it is worth emphasizing once again: automation requires implementation-oriented process modeling, in addition to as-is analysis. With this, process modeling has definitively entered the domain of requirements engineering for software development. See [Staud 2025, Sections 12.3 and 12.5]. |

Prerequisites |

2.4.3 Use of Artificial Intelligence |

|

This section is under preparation. |

|

|

|

3 EPC - Fundamentals of Event-Driven Process Chains |

|

Preliminary note: For all references to [Staud 2025], the following applies: A short version of this book is available on my website at https://www.staud.info/epk2/ep_t_1.php |

|

|

|

3.1 Introduction |

|

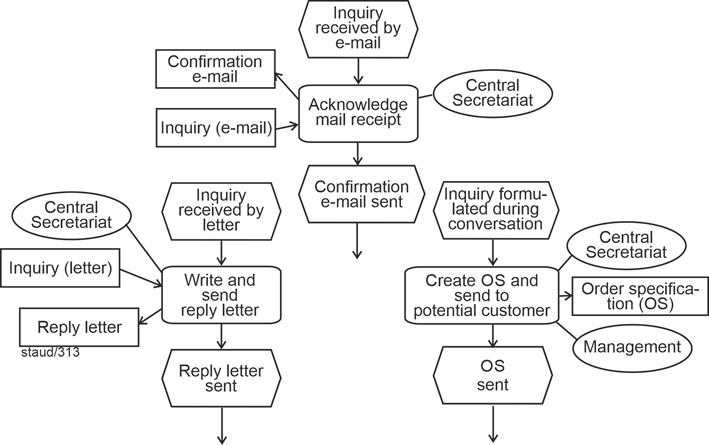

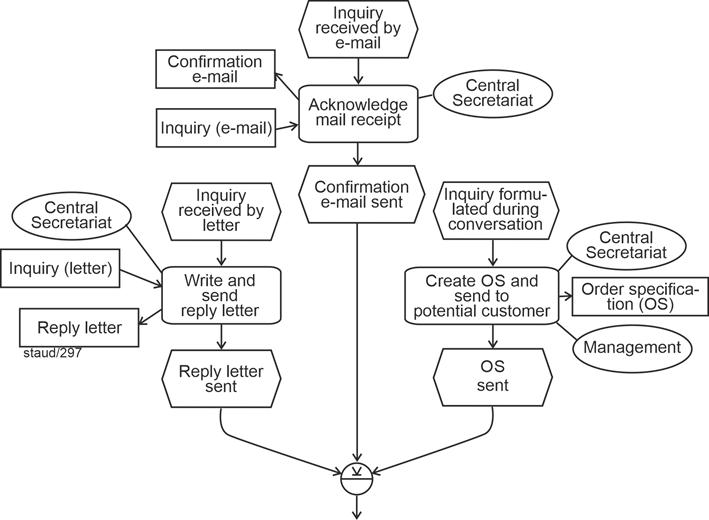

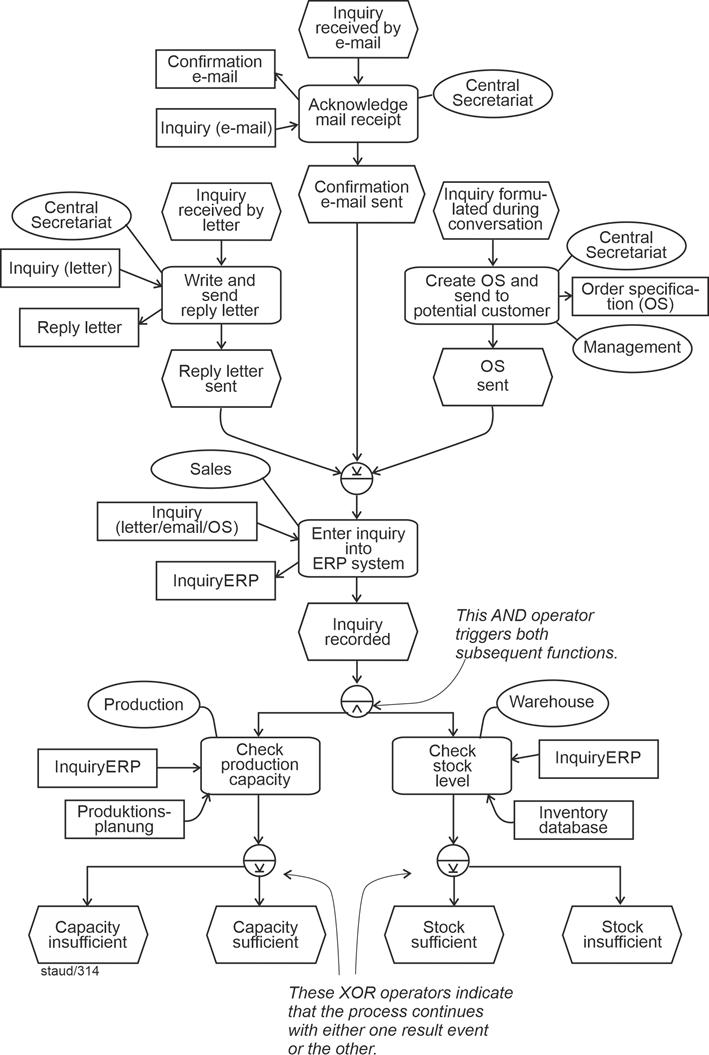

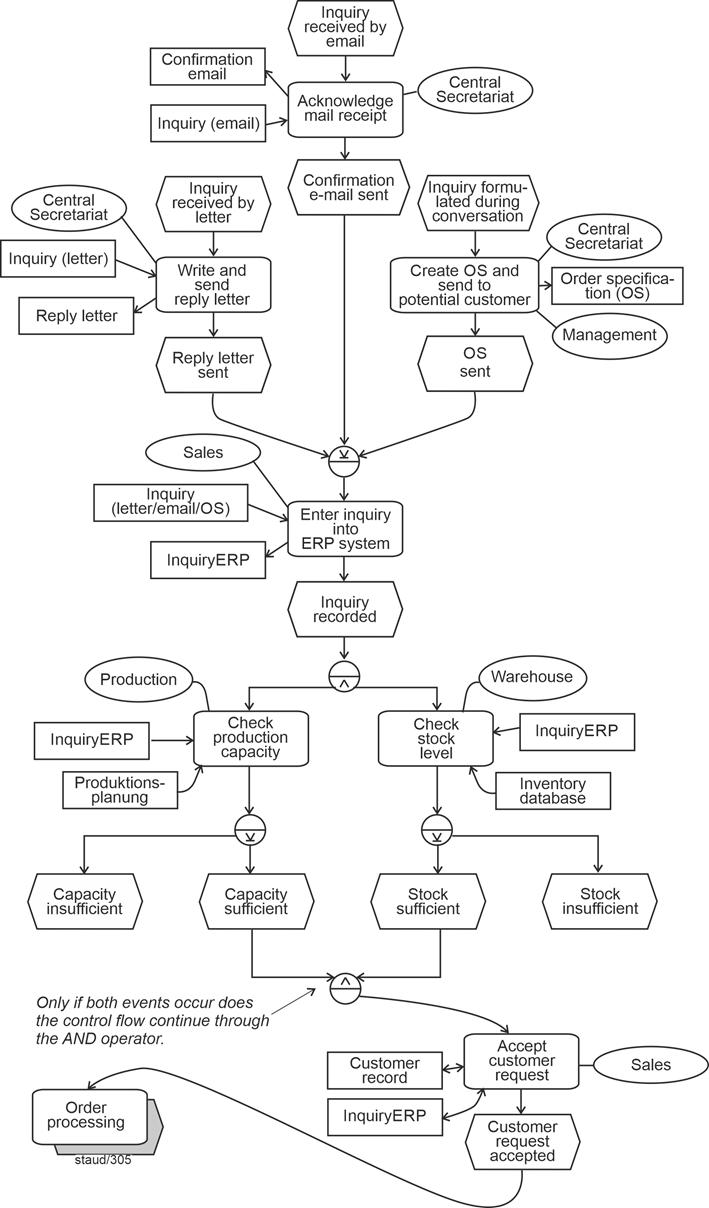

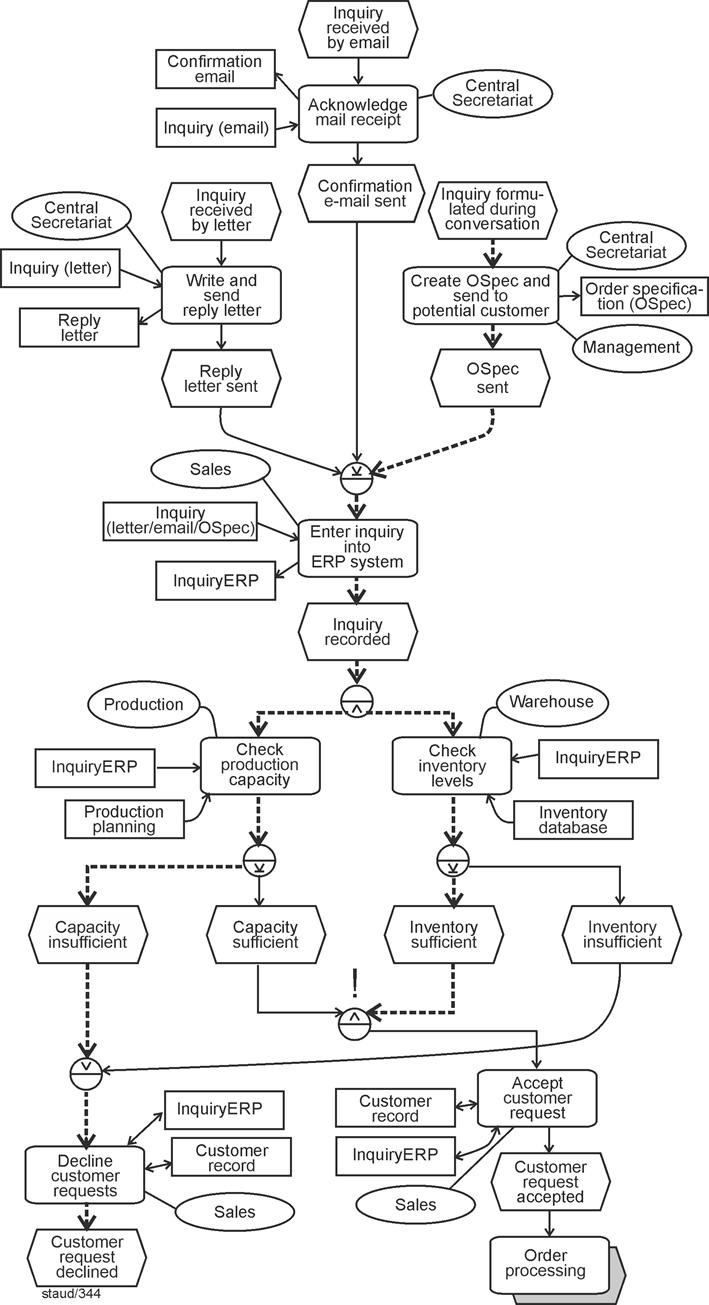

Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs) describe business processes, their activities (referred to as functions), the events that control them, the actors involved (referred to as organizational units), and the information that is used or generated (referred to as information objects). They describe all possible realizations of a process by means of branching and merging constructs (operators, connectors), thereby specifying the so-called control flow of the business process. |

The EPC Method |

They are the tool of choice for the analysis and description of business processes. This applies in particular to as-is analyses of business processes and to the representation of optimized processes (to-be modeling). Only when modeling aims at a higher level of detail - for example, in preparation for the implementation of process-oriented software - are other modeling methods more suitable (see Sections 12.2 and 12.5 in [Staud 2025]). |

As-Is Analysis and

To-Be Modeling |

This method and the associated graphical modeling technique (notation) for business processes were developed by Scheer and his colleagues as part of the ARIS concept (see [Keller, Nüttgens, and Scheer 1992], [Scheer 1997]). For a brief overview, see [Staud 2025, Section 13.1]). |

ARIS

Architecture of Integrated Information Systems |

Event-Driven Process Chains are a semi-formal method. They do not meet the requirements - as will also become apparent later - that must be fulfilled by formal methods or languages. Rosemann expresses a similar view in his contribution in [Mertens et al. 1997, p. 334], where he distinguishes between |

Informal - Semi-Formal - Formal |

- informal methods, for example textual descriptions,

- semi-formal methods, for example Event-Driven Process Chains, and

- formal methods, such as predicate logic.

|

|

The requirements for such a method listed there - representation of control flow, modeling of concurrency, conditional branching, and loops, depiction of data flow, as well as the specification of the involved organizational units and information systems - are readily fulfilled by Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs). |

|

Despite the fact that this notation is not fully formal, the term syntax is also used here to refer to the rules governing the correct construction of Event-Driven Process Chains. |

Syntax |

3.2 Elements |

|

In [Scheer 1997], during the derivation of the ARIS concept, the elements of business processes were identified. In the concrete formulation of the EPC method, he summarizes them as follows: |

Four Elements plus Control Flow |

- Functions

- Events

- Organizational units, and

- Information objects

|

|

In addition, control flow and - to a limited extent - data flow are taken into account. |

|

3.3 Functions |

|

All activities that must be carried out within a business process are captured as functions in an EPC as part of process modeling. That is, the overall task of the business process (e.g., prepare a cost calculation) is decomposed into individual subtasks, with more or less detail. The decision regarding the scope of elementary activities represented by an individual function is left to the modelers. Consequently, the subjective factor of modeling discussed in [Staud 2025, Section 2.2.1] remains applicable. |

What Is Performed? |

For human actors, functions describe their operational activities; for an information system, they represent something like a transaction or a business function module. |

|

In this modeling approach, the time consumption of functions is not quantified. That is, no indication is given of how much time (maximum or minimum) is required to perform the activities captured by a function. Nevertheless, the temporal dimension of a business process is integrated into this modeling approach in multiple ways. See Sections 6.3 and 6.4 in [Staud 2025]. |

Time Consumption |

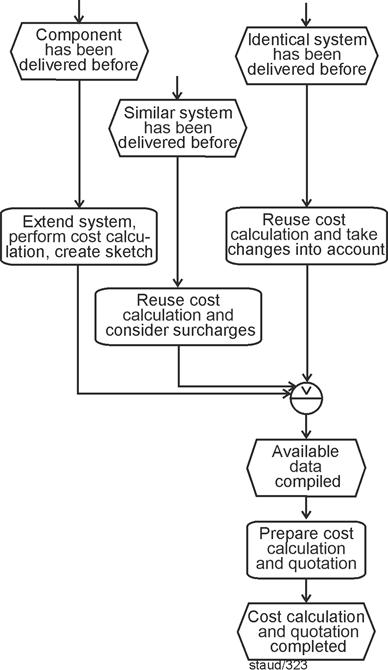

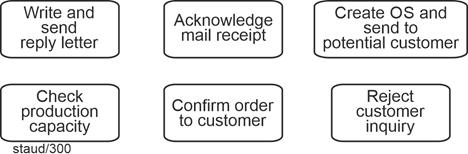

The graphical representation of functions is a rectangle with rounded corners and a label centered within the rectangle. See the following figure. |

|

|

|

Figure 3.3-1: Functions - Graphical Representation |

|

The naming of functions should be done in such a way that the activity is clearly recognizable, preferably by combining a noun and a verb. Examples include: |

|

- Check feasibility or Feasibility check

- Prepare a cost calculation

- Reject an order

|

|

3.4 Events |

|

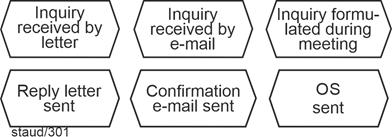

In this context, events are understood to be events that are relevant from a business perspective. These events influence and control operational processes within an organization in one way or another. Examples include: |

|

- Order received

- Quotation is valid

- Order confirmation sent

- Transfer prepared

- Customer inquiry rejected

- Customer is new (as the result of an appropriate check)

|

|

Events should be named exactly as in these examples, that is, as propositional statements. This clearly conveys their event character. |

|

For defining events in process modeling, we can rely on the everyday notion of an event, with the additional requirement that the events must be business-relevant and meaningful for the business process under consideration. |

|

This definition becomes more specific when considering that process modeling assumes a close relationship between functions and events. For example, the execution of a function always leads to an event (such as "completed"), or to several events. |

Function - Event - ... |

Events are related to a specific point in time, although this point is usually not explicitly specified. In common representations, it is determined only by embedding the event into a chain of activities (functions) and events - that is, into a branch of the control flow. In other words, events trigger functions and are the result of functions. This is the reason why Scheer writes: |

|

"An event can be defined as the occurrence of an object or a change in a specific attribute value." [Scheer 1998, p. 49], translated by the author. |

|

Here, Scheer uses the term objects to refer, for example, to products. Events in this sense can arise from preceding activities as descriptions of possible outcomes, but they can also refer to subsequent processing steps or - seemingly out of nowhere - originate externally (IT system was hacked, Order received). |

|

The set of all events that are possible within an organization and its environment is referred to as the organization's event space. |

Event Space |

An event is always also a statement that must be made somehow and by someone. Actions precede it, and in most cases further actions follow it. These are captured here using the concept of functions introduced above. |

|

Events, like functions, can be aggregated or decomposed. Consider the deliberately high-level event "The company has not generated any profits." This could just as well be described by "events" such as "Sales decreased by x%", "Costs amounted to y", and so on. In principle, the level of aggregation of events should be aligned with that of the functions. |

Aggregation of Events |

Two events of every business process deserve special attention: the start event and the end event (or final event). A business process begins with the start event - prior to this, there are no actions with respect to the individual business process - and it concludes with the end event. In principle, a process may also have multiple start events and multiple end events. |

Start and End |

The graphical representation of events in Event-Driven Process Chains is a horizontally stretched hexagon with the name of the event centered inside the shape. |

|

|

|

Figure 3.4-1:Events - Graphical Representation |

|

3.5 Organizational Units |

|

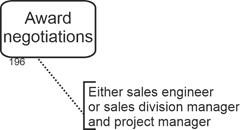

Organizational units are used to specify who performs the task captured by a function. This may be a classical organizational unit (department, position, etc.) or the application software that realizes the function in an automated manner. Application software may be conventionally programmed, such as typical ERP software, or implemented using modern AI techniques. |

Who Performs the Task? |

When functions are performed by humans, organizational units are often defined at a very fine level of granularity today - especially when staffing levels are already low and or when the organization is moving away from a traditional hierarchical structure. In such cases, it may even be appropriate to model organizational units at the level of individual positions in order to obtain sufficient explanatory power for the analysis of weaknesses. |

|

Examples of (classical) organizational units in an industrial enterprise include Sales, Human Resources, Production, and Information Services. |

|

The graphical representation of organizational units in Event-Driven Process Chains is an ellipse with the label centered inside. Organizational units are always connected to the function they perform by a non-directional line. |

|

|

|

Figure 3.5-1: Organizational Units and Their Connection to Functions |

|

Design Rule: Organizational Units |

|

In many projects, it is common practice to omit organizational units at a function if they are the same as for the preceding function. If no organizational unit is shown for a function, one must therefore trace upstream to the last occurrence. |

|

[Staud 2025, Section 7.6] discusses several issues related to the specification of organizational units. |

|

3.6 Information Objects |

|

No organization can operate without data repositories that model the organization itself, its business objects, and its informational environment, either in full or in part. These data repositories are therefore of great importance for the execution of business processes. In Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs), this is reflected in the specification of the information that is retrieved (received) and used, or that is created, at each function. This may include customer data, details from a previously prepared quotation, current market prices, or any other information that is relevant for a particular segment of the business process. |

Which Information Is

Required by a Function? Which Information Is Created? |

In the EPC method, such data are referred to as information objects (IO) and are associated with the function for which they are required. For example, the following information objects may be assigned to a function Order Processing: |

IO Supporting Business

Processes |

- information about customers

- information about the quotation

- information about materials

- information about terms and conditions

- information about the customer order

- information about required parts, and so on.

|

|

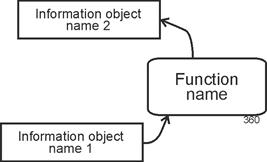

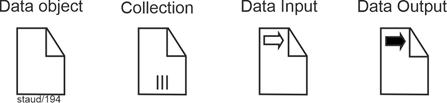

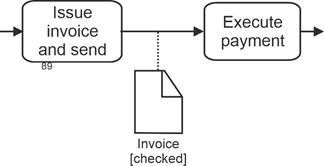

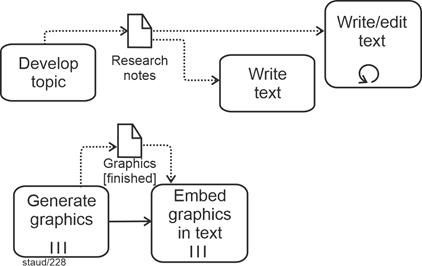

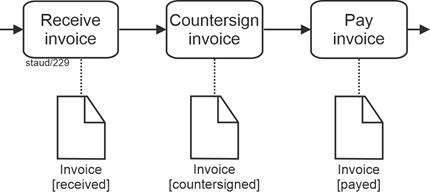

Information objects are graphically represented as rectangles with the name centered inside. Each information object is connected to a function. In the relationship between information objects and functions, an arrowhead is used to distinguish whether the information flows into the function - that is, is required for task execution - or whether it is created by the function. The arrowhead thus indicates the direction of the information flow. |

Rectangle with Arrowed

Line |

|

|

Figure 3.6-1: Information Objects and Their Connection to Functions |

|

As will be seen below, data flows (in the sense of data flow diagrams) are captured in this way only if this part of the modeling is carried out very carefully, which is often not the case in practice. |

|

Information objects do not have to consist solely of data from databases. In principle, any information on any type of information medium can be taken into account. Explicitly indicating non-electronic media (in the context of an as-is analysis) can even provide an initial indication of opportunities for business process optimization. |

Information Media of

All Kinds |

In general, information objects also provide indications of the degree of automation of the business process under consideration. In non-automated or only partially automated segments, information objects are often (though not always) non-digital. |

IO and Automation |

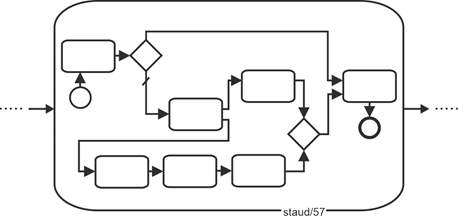

3.7 Control Flow |

|

The construct of control flow was already introduced in the introduction to this chapter. It can now be specified more precisely. The possible sequences of events and functions within a business process, starting with start events and ending with end events, are referred to as the control flow. |

The Invisible

Organizing Hand |

A single concrete execution of a process is referred to as an instance. Accordingly, the control flow can be understood as the set of all possible instances of a business process. Further details on instances, and especially examples, can be found in Section 5.5. |

Instances of a Business Process |

A note for readers familiar with object-oriented theory: there is a certain parallel between the concepts of business process model and business process instance and the concepts of class and instance. The former denotes the abstract, general representation and specifies the overall structure, while the latter refers to a concrete manifestation. Beyond this analogy, however, the comparison does not extend further. |

|

Thus, control flow refers to all possible executions of a business process, including all branches, as required by the semantics of the business process. This is where business rules are expressed, as well as common sense (for example, an offer must be prepared before it can be sent). |

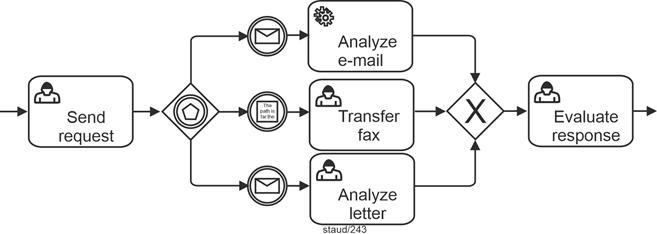

|

Control flow is also related to authority. Internal organizational procedures are, naturally, shaped by this as well. At certain points in a business process, decision situations arise that must be handled by the process actors. Such authority typically does not exist with respect to an organization's external partners. For this reason, the originators of the BPMN method allow only message flows for interactions "to the outside", and not control flows - or, as they are referred to in BPMN, sequence flows. |

Authority |

Events and functions that follow one another in the control flow are connected by arrowed lines. More details on this are provided in the following chapters. These arrowed lines are often also referred to as edges, drawing on terminology from graph theory. Multiple such edges, together with their associated events and functions, form a control-flow branch. Such a branch can extend from a start event to an end event. |

Edges and Control-Flow

Branches |

Business processes, and thus Event-Driven Process Chains, have a direction - from the start event to the end event - which is why it is also possible to speak of upstream (back toward the start event) and downstream (toward the end event). |

upstream and

downstream |

3.8 Operators and Control Flow |

|

The control flow of a business process does not consist solely of simple sequences of events and functions, but also includes branching of control-flow paths and their merging. This occurs, for example, when several activities must be carried out "in parallel" in order to achieve a goal, or when alternatives exist - either one activity or another leads to the goal. The same applies to events. In some cases, alternative events may trigger the same activity, or multiple events together may constitute the condition for the start of an activity. |

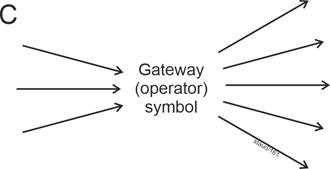

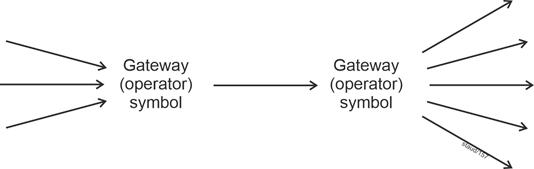

Operators, Connectors |

To represent these structural characteristics of business processes and Event-Driven Process Chains (EPCs), operators (sometimes also referred to as connectors) are required. |

|

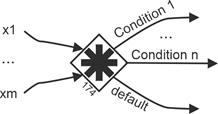

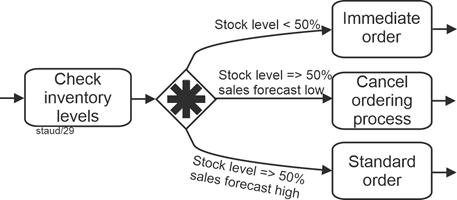

For modeling business processes with EPCs, three operators are sufficient. Their names and graphical symbols are as follows: |

|

- AND:

- OR:

- Exclusive OR (XOR) - also referred to as XOR:

|

|

These are n-ary logical operators, meaning that at least two elements are always connected. The following rule applies: either events are connected to events or functions are connected to functions. |

|

Note |

|

Operators can only connect events with events and functions with functions - not events with functions. |

|

Connected Events |

|

Numerous examples of elementary connections are presented in Chapter 4. |

|

For events, the operators have the following meanings: |

|

- AND: all connected events must occur before the control flow continues

- OR: at least one of the connected events must occur before the control flow continues

- XOR: exactly one of the connected events must occur before the control flow continues

|

|

Connected Functions |

|

For functions, the operators have the following meanings: |

|

- AND: all connected functions must be performed before the control flow continues

- OR: at least one of the connected functions must be performed before the control flow continues

- XOR: exactly one of the connected functions must be performed before the control flow continues

|

|

A more precise determination of the meaning of the operators depends on their position within the control flow - for example, on whether the connected events occur before or after a function. See the connection examples in Chapter 4. |

|

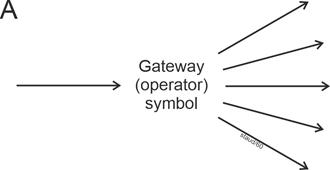

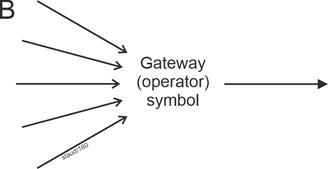

In graphical representations of Event-Driven Process Chains, it is usually assumed, for reasons of clarity, that the control flow is arranged from top to bottom. For this reason, operators are placed in the graphical notation as a circle divided into two halves, for example as follows: |

|

|

|

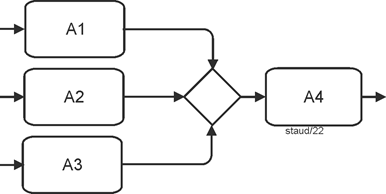

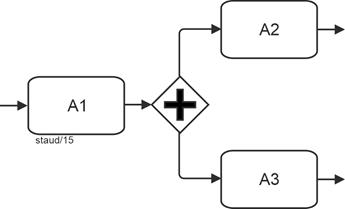

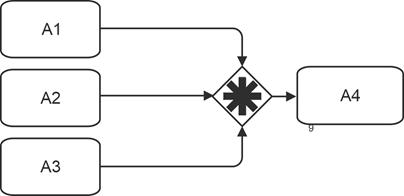

Where an operator is present, there is more than one edge. If no operator is present, there is only a single edge. If there is more than one edge both above and below, operators must be present on both sides. Two examples are shown below: |

|

|

|

The upper half of the operator symbol indicates how the incoming control-flow paths - represented by events or functions - are connected. The lower half does the same for the outgoing edges. |

|

Syntax Rule |

|

Branching and merging of control-flow paths may only be performed using the three operators AND, OR, and XOR. |

|

Two additional terms are used in connection with operators: splitters and joiners. If one control-flow path arrives and several depart, the operator is referred to as a splitter. Conversely, if several paths arrive and only one departs, the operator is a joiner. |

Splitters and Joiners |

3.9 Temporal Dimension and Time Consumption |

|

The sequence of functions within a control-flow branch also expresses a temporal dimension. For example, the function Check inventory level can only be started after the event Inquiry received has occurred; the function Reject customer can only be executed if the event Inventory insufficient has occurred beforehand, and so on. In other words, a function is only started once the preceding one has been completed. |

Temporal Dimension of

a Business Process or an EPC |

Thus, a first fundamental temporal ordering is established in every Event-Driven Process Chain by arranging functions - separated by events - sequentially. This determines their order. However, this specification is not an absolute one that includes a quantified duration, but rather a relative one in relation to the other functions. |

Not Absolute, Only

Relative |

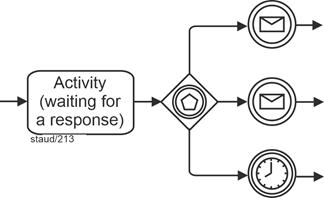

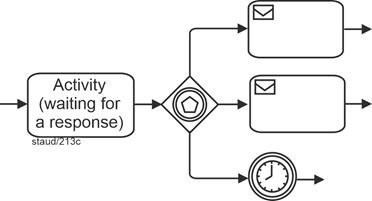

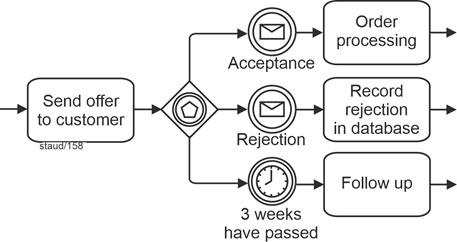

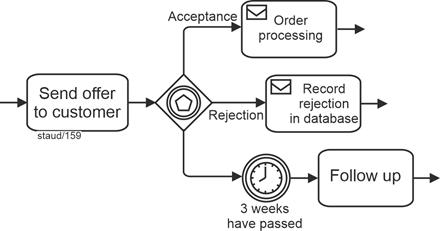

In Event-Driven Process Chains, the time consumption of a function - for example, a specification such as this function must be completed within one day - is generally not captured. An exception arises for functions that express waiting for a response from another party (waiting functions). In such cases, it is entirely conceivable to incorporate an event into the EPC that signals the expiration of time. For example, one outcome of a waiting function could be an event such as Time has expired or Two weeks have passed. |

Time Consumption |

How to "Preserve" Information About Time |

|

Process modeling with Event-Driven Process Chains does not include messages, information channels, or similar elements that could establish a communication network with storage capabilities. The basic philosophy is as follows: information is written to the integrated enterprise database at the time it is created and is later read again in the process when needed. This also corresponds to the implementation found in ERP software, provided that it does not include workflow components, which, by their nature, are based on direct information exchange. |

Writing to and Reading

from the Database |

More system-oriented modeling approaches, such as the dynamic components of UML (sequences, activities, state machines, use cases, etc.), partly take different approaches. In these, the concept of message exchange between system elements does exist. The BPMN method also supports message exchange between acting entities, and even includes a broadcast signal, that is, a message sent to all other components. |

|

3.10 Remarks on the Design of EPC Diagrams |

|

The following rules are applied in this text to the design of EPCs and to the presentation of extensive figures: |

|

- Consistent organizational units. If the organizational units remain the same for a subsequent function as for the preceding one, they are not shown. This serves to improve readability. If no organizational unit is indicated for a function, it is therefore necessary to look upstream to the first function for which such an assignment is shown. This principle is not applied consistently throughout this text, in order to increase the explanatory power of the respective EPCs. Consequently, if a situation becomes unclear or if the last function with an assigned organizational unit lies far upstream, organizational units are nevertheless added.

- Transport of information. For information objects that are merely transported and neither created nor read, no arrowheads are shown in the Event-Driven Process Chains. This is a deliberate decision by the author intended to make information transport activities easier to identify. See also [Staud 2025, Section 7.1].

- Function - function - function - ... In many organizations, it is common practice to omit events in a simple (non-branching) sequence of events and functions. This approach is not adopted here - since the primary focus is on conveying knowledge of the EPC method and the Event-Driven Process Chains presented here are not as large as those typically found in organizational projects.

|

|

|

|

4 EPC - Basic Patterns |

|

|

|

4.1 Possible Arrangements |

|

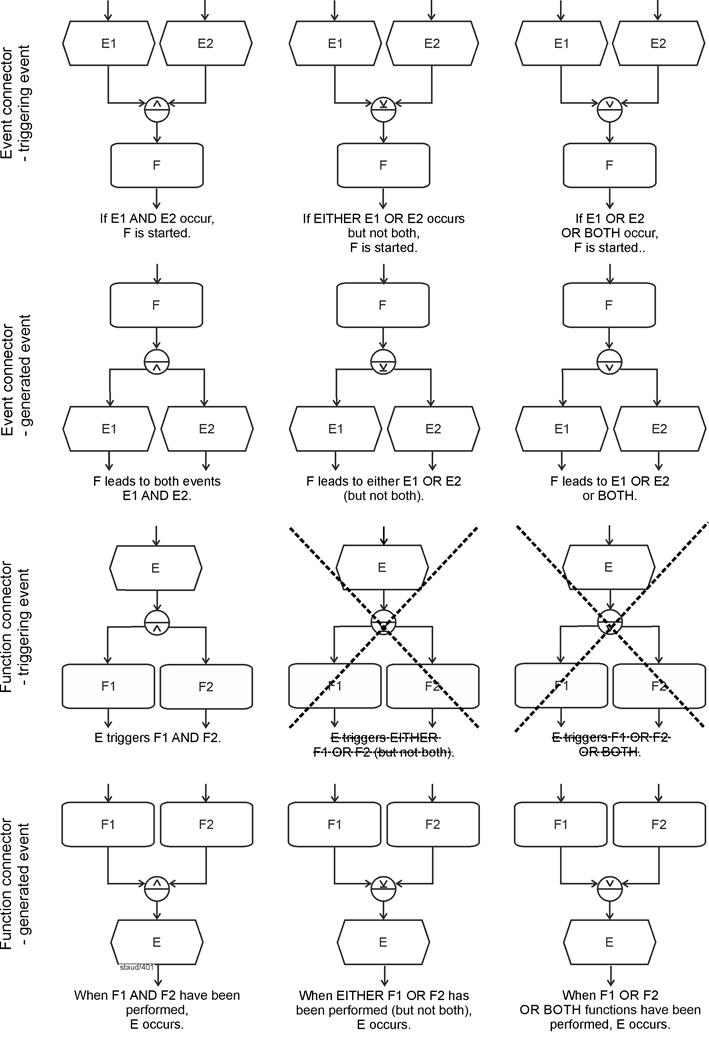

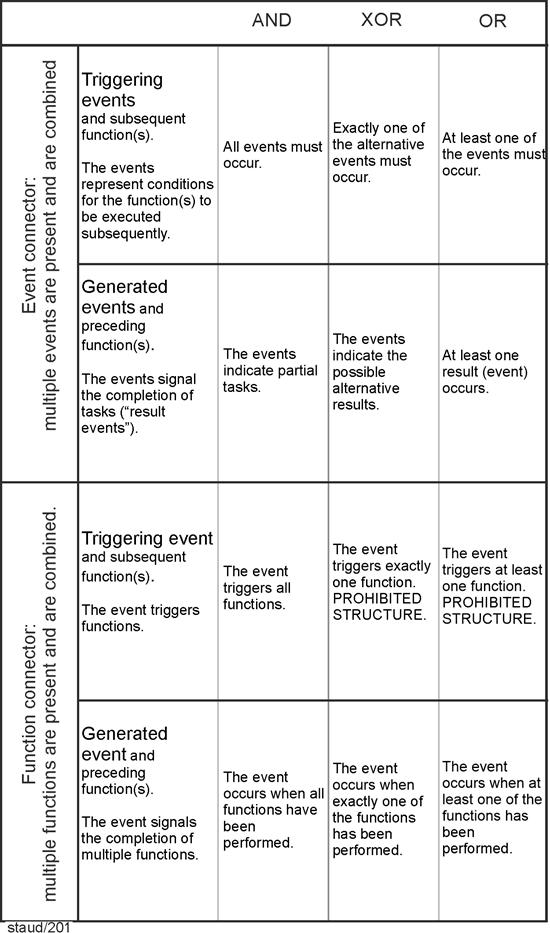

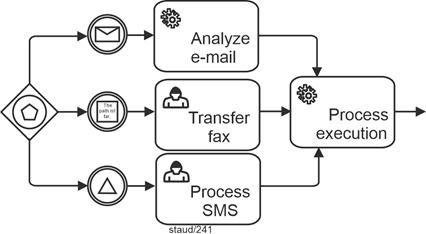

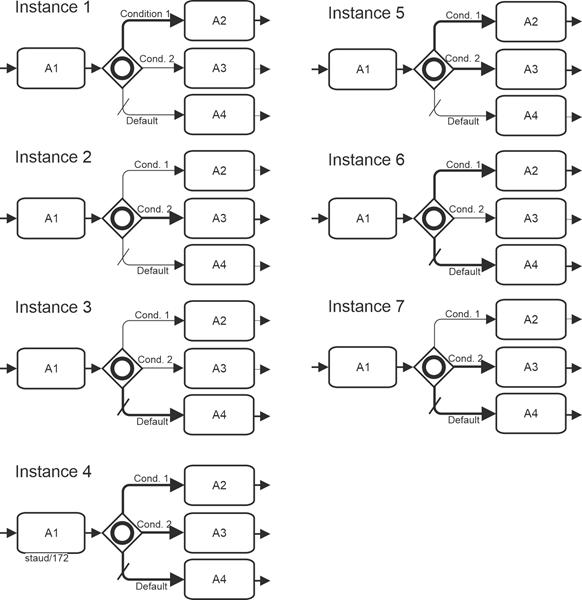

This section examines the ways in which events (E) and functions (F) can follow one another in the control flow when they are connected by operators. For each of the three operators, we distinguish, first, whether events or functions are being connected, and second, whether the events in the respective EPC fragment precede or follow the functions. This yields the twelve variants shown in the following figure. |

All Possible

Arrangements of E and F in the Control Flow |

The figure presents the possible combinations in an abstract form, using labels such as E1, E2, ... for events and F1, F2, ... for functions. In addition, only two events or two functions are shown for each operator connection. Content-related example fragments follow in the subsequent sections. |

|

To improve readability, the control flow is always arranged from top to bottom, with one side of the operator symbol at the top and the other at the bottom. |

|

For arrangements in which events come first and functions follow, we refer to the events as triggering events (tE). See rows 1 and 3 in the following figure. The meaning of this term becomes clearer in the examples below, where it can be seen that in certain arrangements the events effectively serve as triggers for the functions that follow them. |

Triggering Events |

In the opposite case, where events follow functions, we refer to them as resulting events (rE). In such cases, the events are, so to speak, produced by the execution of the function. See rows 2 and 4 in the following figure. The examples below will also help clarify this meaning. |

Definition: Resulting

Events |

The crossed-out connections in the figure are not permitted; more on this below. |

|

Note: The EPC fragments shown here are typically excerpts from larger EPCs. The arrowheads at the top and bottom indicate how these fragments connect to the surrounding model context. |

|

|

|

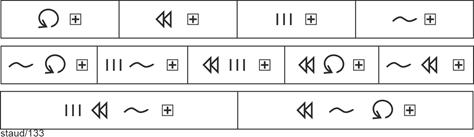

Figure 4.1-1: Possible Connections of Events and Functions Using Operators |

|

E: Event, F: Function |

|

In the following, the arrangements shown in the table above are discussed sequentially, from top to bottom and from left to right, each accompanied by at least one meaningful example. |

|

4.2 Event Connections with Triggering Events |

|

Event connections with triggering events always mean that events act as conditions for the function to be executed next (there may also be several functions). |

Events as Conditions |

4.2.1 AND |

|

If triggering events are connected using the AND operator, all of them must have occurred before the control flow continues beyond the operator. In such a situation, the events have the character of joint conditions for starting the function: the function is only started once all events have occurred. |

Joint Conditions |

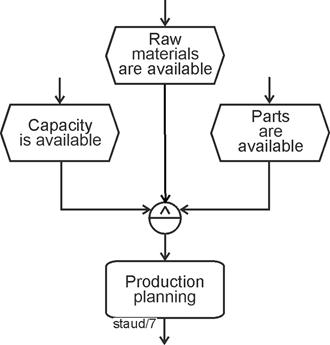

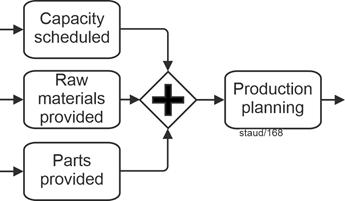

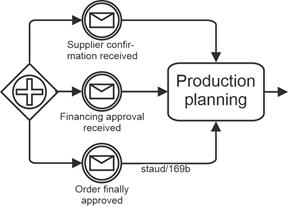

In the following example, the situation after an order has been received is considered. Production planning is only started once capacity is available and the necessary raw materials and resources are present. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.2-1: Event Connections / Triggering Events / AND |

|

In this way, rules and regulations that apply to the respective process can be incorporated into the model. |

|

4.2.2 XOR |

|

When triggering events are connected using an exclusive OR (see the following figure), they represent alternative events for which exactly one must occur for the control flow to continue and for the subsequent function to be started. The triggering events thus represent conditions of which exactly one must be fulfilled for the business process to proceed. |

Alternative Conditions |

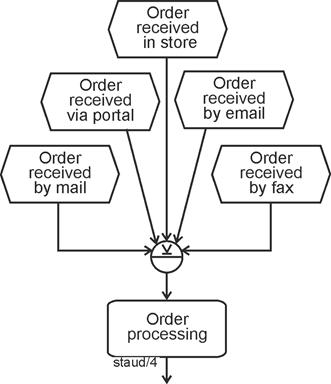

In the following example, orders are considered. It is assumed that these may have been received by letter, via an online portal, in a physical store, by email, or by fax. This is modeled by start events that are, by their nature, alternative - which corresponds to the logic of the exclusive OR. Thus, order processing is started only if one of these events has previously occurred. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.2-2:Event Connections / Triggering Events / XOR |

|

4.2.3 OR |

|

Event connections using the logical OR mean that at least one of the parallel events must occur for the subsequent function to be started. As the wording already indicates, several or even all events may occur. |

At Least One Event

Must Occur |

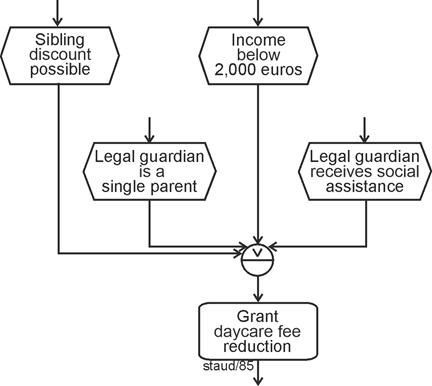

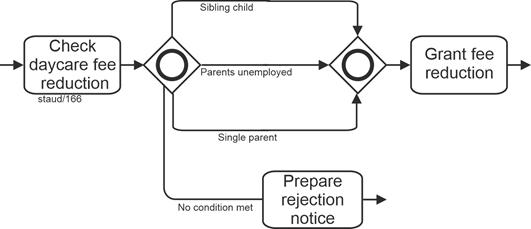

The following example concerns the question of whether parents may be granted a fee reduction when their child attends a daycare center. The criteria for this were formulated as events. A reduction may be granted if ... |

|

- ... a sibling already attends the daycare center (sibling discount).

- ... the income of the legal guardians is below USD 2,000.

- ... the legal guardian is a single parent.

- ... the legal guardian receives social welfare benefits.

|

|

If at least one of these events occurs - that is, if at least one criterion is fulfilled - the reduction may be granted. The OR operator can therefore be used. |

|

This example is fictitious. In practice, the actual set of rules is likely to be considerably more complex. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.2-3: Event Connections / Triggering Events / OR - Example 1 |

|

In this example, the question arises as to why the individual events (criteria) are specified at all. Would it not suffice to use a single event such as Reason for reduction applies following a function that checks this condition? This would certainly be possible. However, it is often desirable to document the various alternatives explicitly in the Event-Driven Process Chain. In such cases, the modeling approach shown above is appropriate. |

Possible Aggregation |

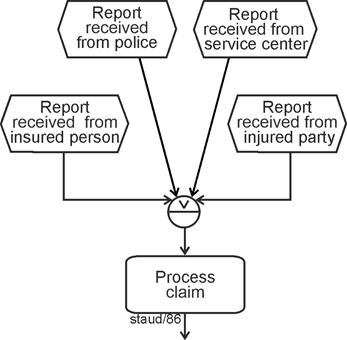

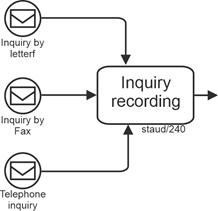

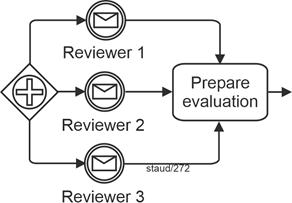

The following second example describes a similar situation in an insurance company. A claim may be reported by the policyholder, the injured party, a service center, or in rare cases even by the police. It may also be reported by several of these "reporting parties" - for example, by both the insurer and the injured party. Here as well, the logical OR is therefore the appropriate operator. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.2-4: Event Connections / Triggering Events / OR - Example 2 |

|

Here too, the OR condition is fulfilled. For the concrete business process, this means in practical terms that potential multiple notifications (the same claim being reported several times) must be handled appropriately. |

|

As already noted above, events connected by OR can always be aggregated. However, when events are modeled in a detailed manner, the intention is to document the possible alternatives and their combinations. This information may also be required elsewhere in the Event-Driven Process Chain. For example, in the fragment concerning the granting of a fee reduction, it may be useful in certain cases to know which criteria were the reason for the reduction, even if this information is not strictly necessary for the further process flow. In such a case, however, this information storage would need to be modeled explicitly using information objects. |

Aggregation or

Detailing |

4.3 Event connector with generated events |

|

In this configuration, the events signal the execution of a function (or several functions); they indicate partial tasks or possible results. |

|

4.3.1 AND |

|

With the logical AND, the subsequent events represent partial tasks that result from the execution of the function. These are intermediate results that are considered sufficiently important to be explicitly represented in the model. Formally speaking, all subsequent events must occur (all partial tasks must be completed) before the business process can continue. |

Partial tasks with AND |

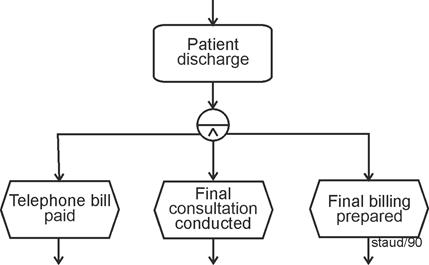

The following example is taken from a real-world hospital context and addresses the process of discharging patients after an inpatient stay. For the sake of simplicity, it is assumed that this includes paying the telephone bill, conducting a final consultation, and preparing the final billing. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.3-1: Event Connections / Generated Events / AND |

|

In this context, the AND operator does not indicate parallelism (of subtasks), but merely that all of them must be completed before the next function can be started. Subtasks can also be modeled in other ways. Triggering several functions after an event, as shown in the introductory example, can likewise be interpreted as triggering subtasks. See [Staud 2025, Section 6.2] for a more detailed discussion of subtasks. |

No Parallelism in the

Technical Sense |

4.3.2 XOR |

|

With the exclusive OR, event connections with generated events indicate that the events represent possible alternative outcomes of the preceding function. That is, exactly one of the events must occur for the control flow to continue. |

Capturing Alternative Outcomes |

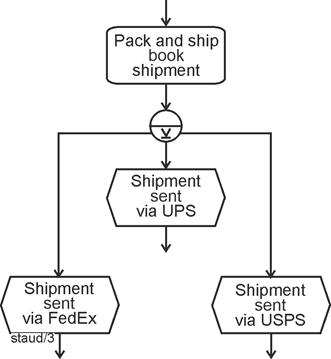

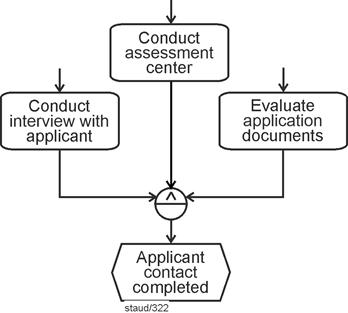

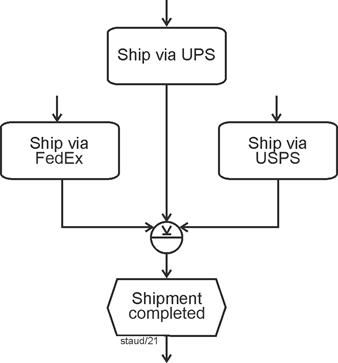

The following example describes - in a publishing company - the process that leads to the shipment of books. After a shipment has been prepared for dispatch, it is sent using one of the transport companies. Naturally, only one can be selected, since the shipment can only be sent once. The events therefore represent possible alternative outcomes. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.3-2: Event Connections / Generated Events / XOR |

|

Shipping providers:

UPS (United Parcel Service, Inc.) - US-based parcel and logistics company

FedEx (Federal Express Corporation) - US-based global express and logistics provider

USPS (United States Postal Service) - US public postal service offering mail and parcel delivery

[ChatGPT 5.2 / Jan 2026] |

|

4.3.3 OR |

|

The syntax of the OR operator in this configuration indicates that at least one event must occur for the control flow to continue. In other words, a non-empty subset of the events must occur. |

|

From a semantic perspective, as is always the case with generated events, the events signal the completion of tasks. Here, however, they do not represent subtasks (as with AND) or alternative tasks or outcomes (as with exclusive OR), but rather tasks or outcomes that may occur individually or together, in any combination. |

Completion of Tasks |

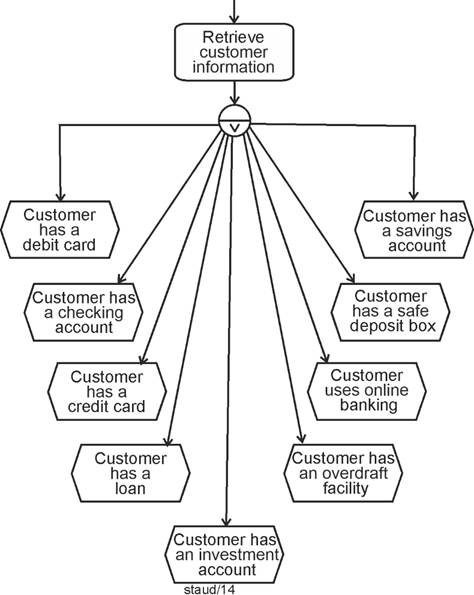

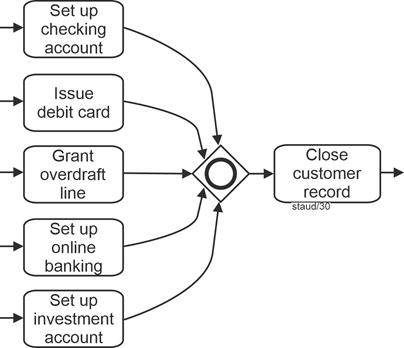

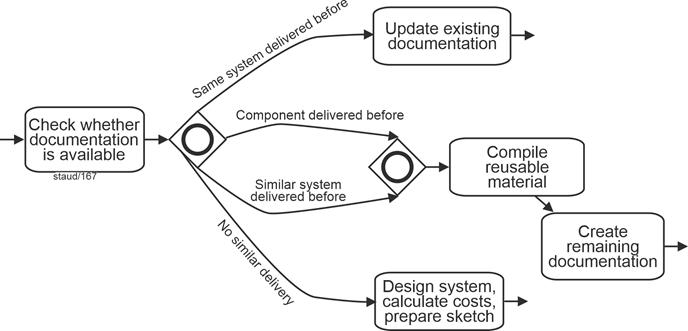

The following EPC fragment shows an example. In a customer inquiry, it is determined which services a customer uses. Since the person is already a customer, at least one result exists. The inquiry may therefore lead to any number of results. This situation can be modeled using a function followed by an OR operator and corresponding result events, as shown in the following figure. |

|

|

|

Figure 4.3-3: Event Connections / Generated Events / OR |

|

Short explanation of some of the banking products

- Checking account: A checking account is used for everyday financial transactions, such as receiving salary payments, paying bills, and making transfers.

- Debit card: A debit card is directly linked to the checking account. Payments and cash withdrawals are deducted immediately from the account balance.

- Credit card: A credit card allows the customer to pay without immediate withdrawal from the bank account. Expenses are billed later, usually once a month.

- Savings account: A savings account is used to store and save money. It is typically not intended for daily transactions.

- Overdraft facility: An overdraft facility allows the customer to spend more money than is currently available in the checking account, up to a defined limit. Interest rates are usually high.

- Loan: A loan is a larger amount of money provided by the bank for a specific purpose and repaid over a longer period of time.

- Investment account: An investment account is used to hold and manage securities such as stocks or mutual funds.

- Safe deposit box: A safe deposit box is a secure storage space at a bank for valuables or important documents. |

|

For generated events connected by an OR operator, the question often arises whether the events connected by OR are independent of one another, that is, whether each event can truly occur independently of the others in any combination. This can also be illustrated using the example above: |

Independence? |

- Online banking requires either a checking account or a securities account.

- An EC card requires a checking account.

- A loan is only granted if the borrower has an account.

|

|

There may be many such dependencies. By using the OR operator, these dependencies are deliberately not resolved. If this internal structure were also to be modeled, the EPC would become more complex. |

|

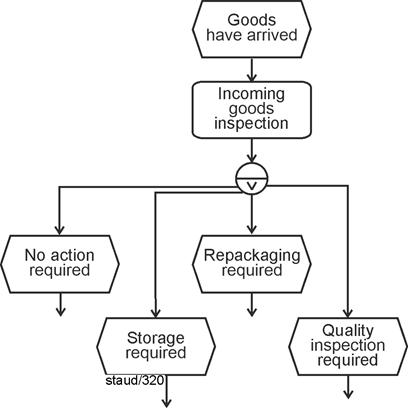

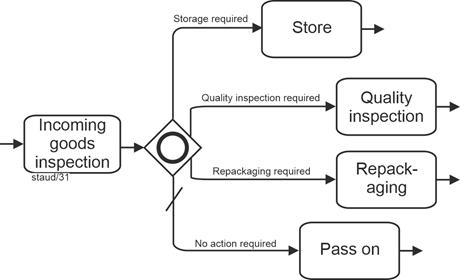

The domain-specific example shown in the following figure illustrates a similar situation. In this company, incoming goods inspection may lead to the goods being stored, repackaging being required, quality control being involved, or several of these activities occurring in any combination. So far, this corresponds to the "pure" logic of the OR operator. If one adds to these possible inspection results the event that signals that none of the other actions is required (No action required), the Event-Driven Process Chain shown in the following figure emerges. This is a natural and commonly used modeling approach. However, in this case the OR operator is no longer fully satisfied, because the event No action required cannot occur in combination with the others. The events are no longer independent of one another. |

|

This syntax therefore contradicts the OR operator, at least in its semantic interpretation, that is, when the meaning of the events is taken into account. Purely syntactically, if the only requirement is that at least one event must occur, the OR condition is still fulfilled. |

Syntax vs. Semantics |

|

|

Figure 4.3-4: Event Connections / Generated Events / OR

Incoming Goods Inspection |

|

The fact that events connected by OR should, in principle, be freely combinable, but that this is not always implemented (or possible) in practical modeling, can be described in terms of the independence or non-independence of events. |

Independence of Events |

A group of events connected by OR is independent of one another if the semantics allow the events to occur in any combination. |

Definition |

How such a structure - incorrect in the strict sense of the operator - can be transformed into a correct one is shown in [Staud 2025, Section 7.3]. |

|

4.4 Function Connections with Triggering Events |

|

Function connections with triggering events always mean that the occurrence of an event starts subsequent functions. This may be exactly one of several functions (XOR) (?), several functions together (AND), or at least one function (OR) (?). The question marks indicate that there are issues here that still need to be addressed. |

Event Triggeres Functions |

4.4.1 AND |

|

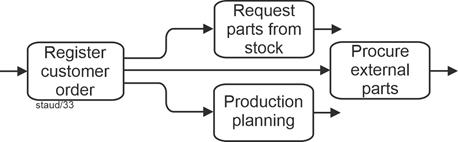

That an event directly triggers exactly one of several functions is generally considered undesirable in process modeling, because an event is not an activity in which a decision is made as to which function should be started. This will also be the topic of the next two sections (XOR, OR). With AND, however, there are no such problems. An event may lead to the parallel start of two or more functions. |

Well-Known: One Event

Triggers Several Tasks |

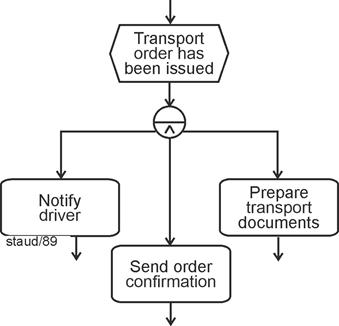

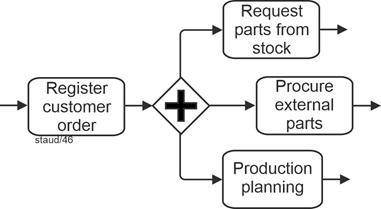

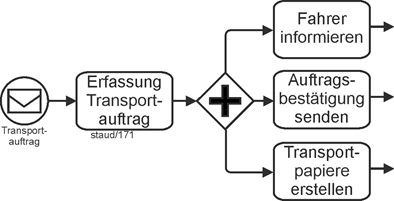

The following example illustrates this. In a freight forwarding company, once a transport order has been issued, the driver must be notified, the order confirmation must be prepared, and the transport documents must be created. In this case, one can certainly assume that there is an order to these activities, but this order is deliberately not modeled when using the AND operator. |

No Order - or the

Deliberate Omission of Order Modeling |

|

|

Figure 4.4-1: AND / function connector / triggering event |

|

As always with the logical AND, the parallel arrangement does not mean that the tasks are actually carried out in parallel (certainly not in a technical sense), but only that they are started together. |

|

4.4.2 XOR - Not Permitted |

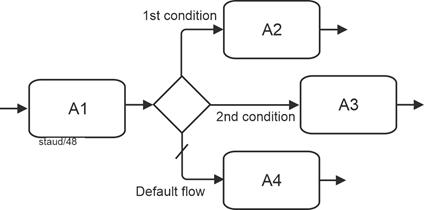

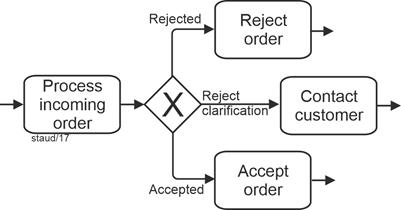

|

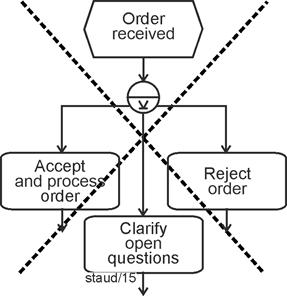

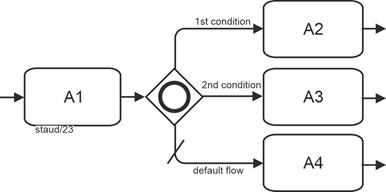

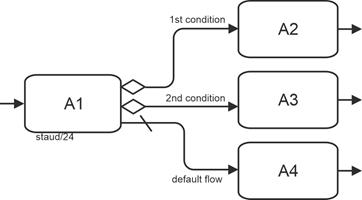

The following configuration is one that is not permitted by the originators of the EPC method. It concerns events that are followed by an XOR operator, thus triggering exactly one of several functions connected by exclusive OR. |

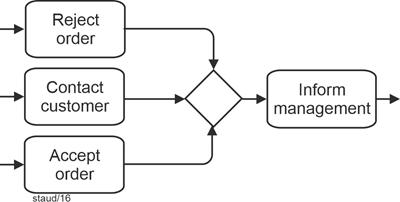

Missing Decision Function |

Let us consider the following example of an order being received. The event Order received is followed either by Accept order, Reject order, or Clarify open issues. If this situation is modeled as shown in the following figure, the EPC may appear appealing due to its simplicity. However, even brief reflection makes it clear that an important part of the real business process has not been modeled: decision-making, feasibility analysis, and similar activities. The EPC, so to speak, "jumps" directly from the event to the execution of one of the functions. |

|

|

XOR - not permitted |

Figure 4.4-2: Function connector / triggering event / XOR without decision function |

|

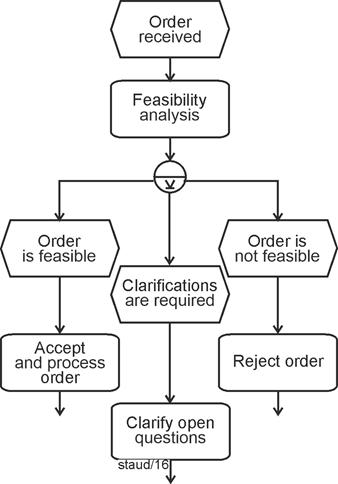

This is the reason why such a structure is, in a sense, prohibited. If it occurs, it must be extended by a function that models the decision process, and by events that express the possible outcomes of this decision process. The fragment shown above must then be modeled as in the following figure. |

|

|

Correct Solution with

a Decision Function |

Figure 4.4-3: Function connections with preceding events / triggering event / XOR - with decision function |

|

With the introduction of the decision function (here: Feasibility check), the EPC also includes the events that indicate the possible outcomes of the decision process. These result events significantly increase the explanatory power of the EPC. |

|

4.4.3 OR - Not Permitted |

|

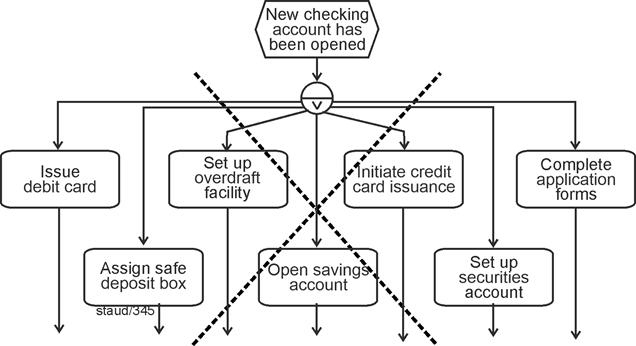

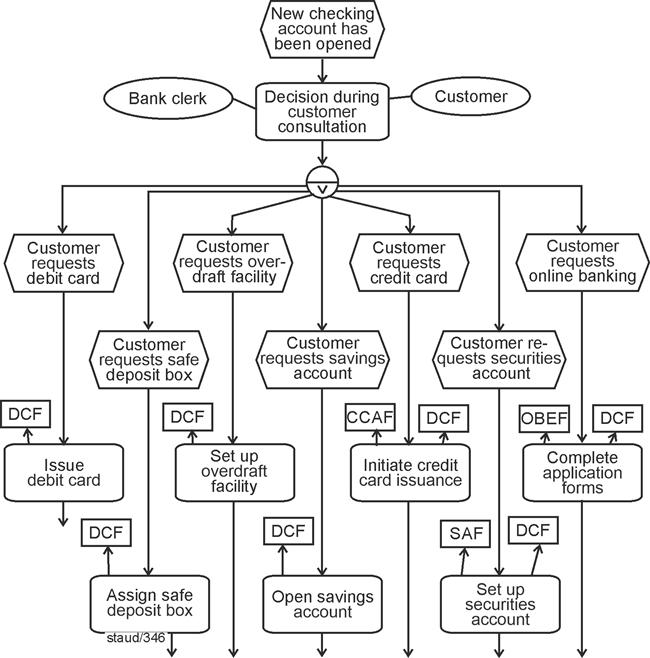

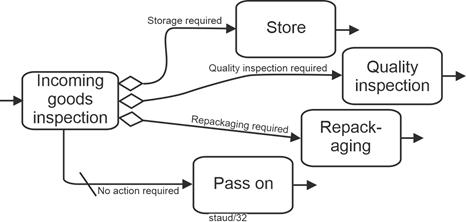

The following OR connector is again a prohibited one, exactly as in the case of the functions triggered by XOR described above. The example illustrates the situation when a new checking account is opened. Once this has been completed, the customer may request various services, ranging from an EC card to online banking. |

Missing decision function |